Joseph A. Petrali: Champion of Champions

Text: Rich Ostrander

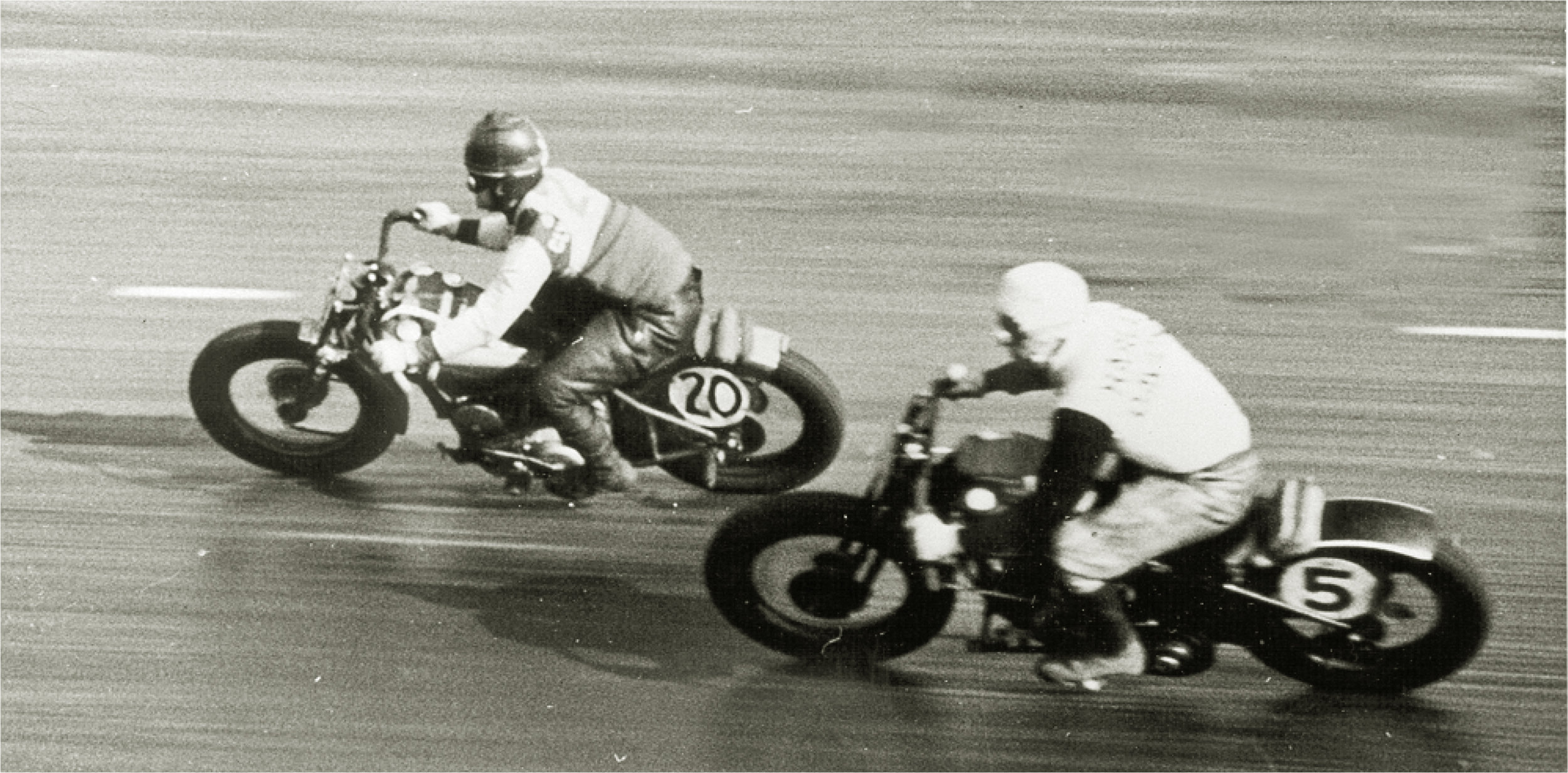

Rust Archive | In 2003, Harley-Davidson Motor Company celebrated 100 years of continuous motorcycle manufacturing. For varied lengths of time during these first 100 years, the factory fielded and maintained a racing team. Of all the riders they had on their payroll, one stands heads and shoulders above the others: “Smokey” Joe Petrali.

The Petrallia family came to this country from Sicily at the turn of the century and changed their name to Petrali on arrival. Several years later they moved to San Francisco where Joe was born in February 1903. Soon after his birth they moved to the same Sacramento neighborhood in which I reside. The family lived near the corner of Stockton Boulevard and Broadway.

When Joe was just 10 years old, he remembered sneaking in and watching the great Don Johns sliding his bright yellow Cyclone around the old State Fairgrounds mile dirt track just off Stockton Boulevard. This same machine was on display at the Antique Motorcycle Club of America’s national meet in Dixon last year.

When Joe turned 13, he went to work for Archie Rife. Archie was the local Indian dealer and an accomplished motorcycle endurance racer. The next year Joe got his first motorcycle, a 1910 30.50 Hedstron Indian that he rebuilt while working for Archie.

He competed and won a local economy run with this machine when his gallon of gas gave him 176 miles. From then on he was hooked. At age 15, he started racing for Rife Motors in unsanctioned outlaw races because he wasn’t yet 18, the legal age to race officially.

In August 1921, Shrimp Burns was killed at a Toledo, Ohio, race, and Santa Ana, CA, Indian dealer Jud Carriker was in charge of Indian’s racing program in the Golden State. He offered Burns’ eight-valve racer to Joe to ride at the 1922 big Fresno event against such heavyweights as Ralph Hepburn, Otto Walker, Ray Weishaar, Jim Davis and Fred Ludlow -- the whole H-D wrecking crew. Joe, now 19, placed second in his first official race and showed he was a force to be reckoned with.

Racing-wise, things shifted into neutral for Joe for the next three years. During this time Joe and his brother Archie entered an endurance run of some importance. Riding six hours on and a half hour off, they broke all existing records after 70 hours. At 76 hours, the officials, who were worn out, stopped the event and declared it a tie.

By this time, Joe was such an accomplished mechanic that Al Crocker hired him for his Indian dealership in Kansas City. Joe won his first “big” race at the Altoona, PA, board track on July 4, 1925. He was supposed to ride an Indian eight-valve machine, but it failed to arrive in time. Before the race, Harley’s

Ace rider Ralph Hepburn was injured in a practice crash. Joe was offered Hepburn’s eight-valve Harley if he could repair it in time. He not only succeeded in repairing it, but he rode it for the win and a record of 100 miles in under an hour. This was the first motorcycle race over 100 mph on a board track. On the strength of this win Joe joined the Harley team and won several races on the track at Laurel MA. Unfortunately, shortly after this Harley-Davidson took a hiatus from racing.

“He stated that he never made more then $60 a week at best while racing for Indian, Excelsior or Harley-Davidson. He did, however, get to keep the purses from the races he won.”

Enter Ignaz Schwinn. After Bob Perry was killed at Ascot, CA, in 1919, Ignaz stopped his company’s support of its racing team. When Joe became available in 1926, Ignaz hired him as a one-man team. Joe stayed with Excelsior until the end in 1931.

Joe’s performance at Altoona, PA, on July 1926, astride his 45-inch Super X, was nothing short of amazing. With a specially built large gas tank, he ran an average of 107.65 mph for 100 miles for the win. The Super X had arrived. The AMA videotape “The Glory Days” has actual footage of Joe and this machine in action.

At a Springfield race in 1927, Joe was seriously injured while trying to avoid Eddie Brink, who crashed fatally in front of him. When Joe was fully recovered, he attended the Capistrano, CA, hillclimb and was beaten by Indian’s new 45-inch OHV twin machine. Joe was so mad, he went back to Excelsior and with

Schwinn’s newly acquired chief engineer, Arthur Constantine (formerly of Harley-Davidson) designed a new race engine. What they came up with was an overhead-valve engine, which used a standard Super X lower end. Joe also built a special motor by grafting early 61-inch M-type cylinders onto a Super X lower end that he dubbed “Big Bertha.”

Joe and his Excelsior teammate Gene Rayne cleaned up in the 45-inch and 61-inch classes. Joe won the 1928 hillclimbing championship, and in 1929 he won again with a record of 31 consecutive victories. He would have won the 1930 Crown, too, except for an incident at the Muskegon MI, championship event.

Timing official Rollie Free incorrectly attached the string to the top of the hill to the timer switch and it didn’t trip on Joe’s run. So Gene moved up and won the title for 1930. During Joe’s entire hillclimbing career, which didn’t end until 1939, he won a total of eight national hillclimbing championships.

In 1931 Ignaz Schwinn ceased Excelsior motorcycle production. Joe then became Harley-Davidson’s sole professional rider for that year. Between 1931 and 1936, Joe won five National championship dirt track titles. He was comfortable aboard his fast single-cylinder “Peashooter” or on the hills with his awesome DAH hillclimber. In 1935, he won all 13 championship races held that year.

“He was comfortable aboard his fast single-cylinder “Peashooter” or on the hills with his awesome DAH hillclimber.”

Alongside William Ottaway and Hank Syvertson, Joe was involved in the development of Harley’s new 61-inch OHV EL motor. In 1937, Harley-Davidson built a special bike to attempt the mile record at Daytona Beach. The bike featured a special 61-inch EL motor with twin carburetors, special cams and high compression, all mounted in a DAH frame. This motorcycle featured streamlining, which was quite innovative for its time. With Joe on board, they walked away with a record run of 136.183 mph, beating Johnny Seymour’s Indian record set in 1926. Joe’s run wasn’t bettered until 1948 when Rollie Free (the same person who cost Joe the 1930 hillclimbing championship) took the record on a Vincent 61-inch twin. Of all the records Joe held, this was probably the most famous.

Joe raced his last race at the Oakland Speedway in 1938 after 19 years in the saddle. He stated that he never made more then $60 a week at best while racing for Indian, Excelsior or Harley-Davidson. He did, however, get to keep the purses from the races he won.

He soon after went to work for Art Sparks in Southern California as a carburetor specialist. Art was a car-building genius. He was involved in constructing cars for Wilbur Shaw, who was very successful at Indy during the mid-’30s and early ’40s. Joe worked for Art until the late ’40s.

“With Joe on board, they walked away with a record run of 136.183 mph, beating Johnny Seymour’s Indian record set in 1926.”

In 1942 Howard Hughes hired Joe as his personal aircraft mechanic. Later on, Joe became his flight engineer on his H-4 Hercules “Spruce Goose” project.

Joe was seated behind Hughes in 1947 when that plane made its one and only flight in the Long Beach, CA, harbor.

In 1949 Joe turned his talents to the Bonneville Salt Flats. Eventually he became the chairman of the U.S. Automobile Club’s record-verification committee.

On Sept. 9, 1960, with Joe as the timer, Mickey Thompson drove his four-engined Challenger 1 to a one-way speed of 406.60 mph on the Bonneville land speed record. In 1964, Joe was running the timer at Bonneville when Craig Breedlove in his three-wheeled jet-powered car almost took out the timing shed he was in. Despite this, Breedlove averaged 536.27 mph and was the first driver to break 500 mph. On the last run, Breedlove’s chutes failed and he went off course. He landed in 18 feet of saltwater and nearly drowned.

Joe passed away in 1973 at the age of 70 while working as a U.S.A.C. official on the annual Mobil Economy Run. He had won close to 70 National Championship victories during his long racing career. When he passed on, he still retained his AMA lifetime membership card, #1.

(This feature originally appeared in RUST #15, June/July 2005.)