The Curious Case of the Corvair

A cornucopia of goodness: 1962 Corvair Monza 900; 2.4 liter, twin-carb, 110 horsepower, four-speed manual trans.

A (not so) brief history of GM’s revolutionary small car

Words+Photos: Mike Blanchard

For years if you went to a car show or concourse there would be all the high-dollar cars front and center: European sports cars, hot rods, muscle cars, antique vehicles, all with pride of place. But the Corvair guys would always be out in back or over in the corner. The weirdo Corvair guys. Half of them engineers or slide-rule types, always slightly defensive about Corvair and ready to proselytize.

Well, those days are passing, and Corvair is stepping into the limelight. Corvair is all over social media. Young gearheads are catching on to these stylish and relatively undervalued cars. There are even air-cooled meets featuring VW, Porsche and Corvair cars all accepted as cousins if you will: branches of the same conceptual tree.

On paper the Corvair should be much more highly regarded. It is of a good vintage (right in the prime of the golden age of post-war American auto manufacture: 1960-1969), it has a successful racing history, the cars look good and were very influential from a design perspective, the drivetrain was groundbreaking and ushered in significant technical advances at GM, and the people involved with developing the Corvair were among the titans of their industry.

Prices have climbed over the years, but compared to its contemporaries the Corvair is still an undervalued vehicle.

I should say at the outset that I own a Corvair. In 1962 my grandparents walked into the Chevy dealer in Glendale, California, and traded in a ’57 Bel Air on a new four-speed 900 Monza coupe. I know, you’re thinking: “They traded in a ’57 Bel Air for a Corvair!” Well, think about it. A Corvair is a much more Jet Age car. It’s way easier to drive, handles better and gets better gas milage. So yeah, it was a step up.

The Corvair passed through my father’s hands and then came to me about 15 years ago. I remember distinctly the first time I drove it. I was a little unsure what to expect when I headed out for the seven-hour trip back to my house. However, I quickly realized what a nice, capable car it is.

It will cruise at modern freeway speeds comfortably. The cabin is roomy and easy to see out of with plenty of leg room. The handling is good even at speeds well over the limit. The engine is punchy with a character that anyone used to a European GT would recognize, and it has a nice exhaust note. All in all, it has proven to be a very enjoyable car.

It has also proven to be quite an icebreaker. Every time I take it out someone tells me about a Corvair they or their parents or brother had. People want to see it and know what it is. And pretty regularly someone shouts, “Unsafe At Any Speed!” when they see it. Although as time goes by that insult comes less frequently.

It is hard to understand today how revolutionary the Corvair was when it was introduced in 1960. It was a big year for small cars in Detroit. Each of the Big Three automakers realized that tastes were changing and there was a growing market for cheaper, smaller vehicles. Ford introduced the Falcon and Chrysler Corp. the Valiant. Both conservative, fairly anachronistic designs, stylistically and mechanically. With the Corvair, Chevrolet suddenly began plowing its own furrow.

And it wasn’t just a couple of cars. Corvair was almost a division within a division at Chevrolet. There was a complete line of vehicles: Sedans, coupes, convertibles, station wagons, vans and trucks were produced.

American manufacturers had long since settled on cars with liquid-cooled, upright engines placed in front and driven by the rear wheels. And here Chevy brings out a stylish, almost European car with a revolutionary aluminum, air-cooled engine mounted in the rear of the car.

The name Corvair was arrived at by taking the front half of Corvette and the last half of Bel Air. This gave a familiar yet exotic turn to the name.

The early-model cars featured a typical skinny steering wheel and a metal dash with aluminum trim.

There are two main groups of Corvair cars: the 1960-64 cars and the 1965-69 cars. The main differences are in the body style, engine upgrades and a fully independent rear suspension with improved springing and a reduced roll center. These changes made the cars handle very well.

The second-model cars are generally regarded as more desirable than the early models despite the fact that the earlier cars were far more influential and historically significant. There is great charm in the earlier cars.

All of the Corvair models — cars, wagons, vans and trucks — used the same basic engine, dubbed the Turbo-Air Six. It’s a horizontally opposed, air-cooled six-cylinder (sometimes referred to as a boxer or flat-six) engine. This engine design features cylinders laid flat, directly opposed to each other with three cylinders on each side of the crankshaft.

In all variations the engine is in the rear of the vehicle behind the rear wheels like a VW or a Porsche.

Over the production run the Monza coupes were the most successful option in both body styles.

Travis Fowler’s eight-door ‘61 Greenbrier van. These have become very popular due to their rarity and utility. Think a VW bus with more power … and more exclusive.

Wagons, vans and trucks are some of the rarest models because Corvair produced relatively few of them.

There are model-year-specific rarities as well. In some years production was less than 1,000 units of particular models, which makes these valuable to collectors.

All told, over the nine-year production run of the Corvair, it is calculated that Chevrolet sold 1,839,439 vehicles. By any measure it was a successful product for the company.

But as noted, Corvairs have lagged behind their contemporaries in value.

Hagerty Insurance is a respected player in the classic car field with its finger on the pulse of values. Their coverage figures and price valuation give an interesting look at Corvair values.

If we look at Chevrolet compact models we can make a fairly apples-to-apples comparison. Let’s compare values of two early cars: the ’62 Corvair Monza coupe and Chevy II Sport Coupe. Both cars with six-cylinder engines and roughly the same horsepower. Then let’s compare two later cars: the ’69 two-door Corvair Monza convertible and a ’69 base model 307 Camaro convertible.

To keep things as equal as we can, we are comparing values in Hagerty’s #3 “good” condition.

The Hagerty Price Guide values a ’62 Monza coupe at $6,800. The Chevy II is valued at $14,400. Twice the value of a Corvair despite the Chevy II being a bland offering and nowhere near as sophisticated as the Monza.

When we look at the 1969 cars the Monza convertible is valued at $15,900. A lot of that value is because there were only 521 of this model made. So it’s a rare car.

By contrast the Camaro convertible is valued at $23,600, or about 30 percent more than the Corvair. And this isn’t even a particularly rare car, Chevrolet having made 17,500 of this model.

Where you see the largest climb in Corvair prices is in the high-end cars and vans. Yenko Stingers, Fitch Sprints, Greenbrier vans, Rampside trucks and turbo convertibles are all doing well.

There have been some strong auction prices for the rarer cars in the last three years. In 2019 Mecum Auctions sold a concourse ’66 Yenko Stinger for $220,000. In 2021 Mecum knocked down a Greenbrier van for $103,400. These are perfect examples of rare vehicles, but in both cases they sold for way over the pre-sale estimate and much higher than their Hagerty Price Guide valuation.

Carl Funk’s super clean ‘63 Monza convertible. Convertible models have been some of the strongest market performers of the Corvair line.

From the beginning Corvair was a cultural phenomenon. But not always in the way its manufacturer felt comfortable with.

Over the years there have been many articles written about Corvair, both pro and con. Almost all of what has been written has in some way made reference to Ralph Nader’s 1965 book “Unsafe At Any Speed.” The book was a consumer safety milestone and it did contain some valid criticism of the U.S. auto industry. Cars are safer with seatbelts, collapsing steering columns and padded dashes.

But there is a chapter that deals specifically with the Corvair, and it is here that Nader got out on thin ice. Nader asserted that GM knew the Corvair was unsafe and sold it anyway with callous disregard for its customers.

The assertion was aimed at the car’s handling and centered around the vehicle’s swing-axle rear suspension, which Nader claimed would allow the rear wheels to tuck under the car in certain situations and cause it to roll over, even at very low speeds. Over the years this has been disproven.

The curious thing is that at the time there were numerous cars using the same style of rear suspension, including Volkswagen, Mercedes-Benz, Porsche and Triumph, but these cars’ reputations didn’t suffer the way the Corvair’s did.

Despite this, the term unsafe at any speed went viral in an age without social media. And it was something GM could never get way from.

The cars do handle differently than a front-engined car. Just like a Porsche or Volkswagen, if you hustle the car into a corner, chicken out and get ham-fisted with the brakes, you will unweight the rear and the ass end will come around. But you have to really push the car to do this. Driven even at modern freeway speeds, with correct tire pressures, the car is well behaved and stable.

Wes Nicholas’ beautiful ‘61 Lakewood station wagon. This is the first year for the wagons which, due to low production numbers, are fairly rare.

It is important to keep the tires inflated to the correct pressure with the rears 10 psi more inflated than the front. This ran counter to car culture at the time. Few people pay attention to their tire pressure at all. And in 1960 many gas station attendants just aired the tires up the way they had always done: same pressure all around.

Unfortunately GM baked in some of the issues the early cars suffered from. In an attempt to save money, just before production started they eliminated the front sway bar, which would have gone a long way toward negating Nader’s accusations.

The bitter irony is that by the time Nader’s book came out Chevy had introduced the new Corvairs with redesigned rear suspension and they handled very well. Nonetheless, consumer advocates banged the drum claiming that the car was a one-car accident waiting to happen, tarring the new cars with false claims based on the old cars.

It is important to note that GM never lost a product liability case concerning the Corvair. They settled the first case brought in ’63 because they realized they were unprepared for their defense. But a settlement is not a court loss. Had they been prepared they would not have lost the case in court.

According to retired Chevrolet V.P. Frank Winchell, Chevrolet was so serious about preparing for future trials that at one point as many as one-third of Chevrolet’s Research and Development personnel were working to describe and quantify the vehicle dynamics of the Corvair. They found out what they already knew: The cars had perfectly acceptable handling characteristics.

The next three cases — Collins, Anderson and Drummond — were all brought by the same law firm. Their technical experts were so poorly chosen that one of them could not correctly describe a four-stroke engine cycle.

By this time GM was very well prepared. In addition to all their vehicle dynamics data they had Stirling Moss and Juan Fangio on the stand as driving experts: You know, two of the greatest racing drivers of all time. (Ed. note: We are actively searching for a transcript of this testimony and we will publish it when we find it.)

At the end of the Drummond trial in 1965, Judge Jefferson summed up: “It is the court’s conclusion that the Corvair automobile of the 1960 through 1963 variety is not defectively designed nor a defective product; that no negligence was involved in the manufacturer’s adoption of the Corvair design.”

In 1972 the National Transportation Safety Administration (NTSA) did an extensive study of the Corvair and found that it was not any more dangerous than any other car sold in the U.S. In fact it was found to be safer than some of its competitors.

Nader’s “unsafe at any speed” claims were repudiated, but he refused to acknowledge the validity of the NTSA study, claiming that it was a whitewash.

Despite the cars’ reputation being cleared in court, and by the federal government, a great many journalists have simply ticked off a stock menu of Nader’s complaints without ever digging any further. It is a great shame because there is so much more to the story. The more you dig the less it looks like Nader was on the mark.

A deeper look shows that Ralph Nader’s claim that the Corvair was unsafe were unsupported by credible evidence. And it is clear that Nader stuck to his assertions in the face of overwhelming evidence to the contrary.

To be sure, GM made some mistakes in their handling of the problem, including allegedly having Nader followed, and this no doubt contributed to the sense of outrage that Nader was able to generate.

But by then the writing was on the wall for Corvair. GM had originally planned to discontinue the Corvair in 1964 and go with the Chevy ll compact car. According to CORSA historian Eva McGuire, “Ironically Nader is to thank for the late-model cars.”

John Heiser’s 1965 140 horsepower Corsa features modified heads to take triple-choke Weber IDA carbs. Many consider the late model Corvairs to be one of the most beautiful American body designs of the 1960s.

GM didn’t want to lose face after getting plastered in the court of public opinion by Nader, so they went ahead with the new-model Corvairs. And they were damn good cars.

The big deal for 1964 was the Mustang, sales of which were so strong that GM had to respond, and they got busy designing the Camaro.

Even though their hearts were not in it (they didn’t do any development after ’65 and didn’t even advertise the ’69 cars), the new-model Corvairs were the best of the whole series. While they didn’t have the horsepower of the V-8 they handled a lot better than a Mustang and were a much sportier car out of the box. After all, a Mustang is just a Falcon with a fancy dress.

From 1959 to 1962 Robert Benzinger was the design engineer for the Corvair engine and later senior project engineer for the Corvair. In 1975 he gave a fascinating speech to the Corvair Society of America (CORSA) convention in which he discussed the history of the cars.

Benzinger summed up the Corvair in an interesting way: “The best overall vindication of the Corvair, I think, is in the undocumented, but indisputable, fact that among GM people - employees, executives, engineers - the Corvair was probably the most popular personal and family car that GM ever built.”

Corvairs were owned by such luminaries as Dan Gurney, Carl Sagan and John Glenn.

But, the fact is that a car like the Chevy ll or the Camaro is a cheaper car to produce than the Corvair. There was almost no development compared to the Corvair because the technology involved was all off the shelf.

Chevy had laid out a fortune on development, production and in defending the Corvair in court. It was a difficult car to make a profit on, and there was always a significant part of management that never liked the air-cooled, rear-engine path. Eventually GM had to bow to market forces and internal company pressure and did what they had to do.

As a result, there are still strong feelings about the Corvair, even now, 50 years after its demise. There is stout defense from the Nader camp trying to protect his legacy. There is anger from Corvair owners eager to defend their beloved cars against Nader’s claims and from what they feel as a lukewarm defense of the model by its manufacturer. And GM is justifiably wary to open up old wounds.

The author’s grandparents bought this Monza coupe new in 1962. It has been kept in mostly original condition with some sensible upgrades for reliability.

History

The genesis for the Corvair goes back to the late 1940s. Ed Cole was an up and coming engineer at Cadillac, and one of the projects he worked on was an experimental air-cooled rear-engine prototype. It was never made but Cole recognized the benefits an air-cooled boxer engine gave in simplicity and packaging.

By the early ’50s Cole was managing Cadillac’s tank plant in Cleveland. The M-42 tanks they were building used a 950-cubic-inch AOS-895-3 supercharged, air-cooled flat six made by the aircraft engine maker Continental.

In their off time, Cole and his friends enjoyed designing engines. Engineers love challenges and pushing the envelope. Like many in the auto industry he and his friends saw that there would be a need for an inexpensive and simple, basic-transportation vehicle in the post-war period. And by now Cole was hooked on the concept of an air-cooled flat six engine.

During the ’50s Chevrolet designed and built experimental platforms and drivetrains to study what type of vehicle might be best to fill this need. At the time imports like Volkswagen were not having much of an impact on the U.S. market, so the cars were typically small versions of the cars they already made, but a number of engine and chassis designs were tried out.

The Corvair began as a design study backed by Cole, who by now was chief engineer at Chevrolet. There were a bewildering number of personnel involved with the Corvair project, but Cole’s influence runs throughout the history of Corvair. The bureaucracy at GM is legendary and the people involved changed jobs, some of them several times, during the development and production run of the vehicle.

Despite Cole’s backing there was opposition to the Corvair concept within GM and Chevrolet management. There were executives who were never sold on Cole’s air-cooled rear-engine concept, and they bided their time.

The project was given the go-ahead by management in 1957. The brief was for a 2,400-pound peoples’ car. Early on, with Cole’s backing, the engineering staff decided to use an air-cooled engine in the rear of the car.

This design offered potential advantages in simplicity and in manufacturing cost (due to the lack of the liquid cooling system) as well as enabling a more roomy passenger compartment and flat floor because there is no transmission tunnel. The design brief called for an automatic transmission with no manual option.

Throughout its development the Corvair project was a closely guarded secret even within Chevrolet. The project was so secret that from the beginning it was disguised as a project for Holden, code named Holden 25. Holden was GM’s Australian division, and Chevrolet occasionally did development work for them so it was a plausible ruse.

To keep it secret within the building, the team went so far as to use Holden drafting paper, Holden purchase orders and Holden stationery. In fact, many of the early spares for the first Corvairs bear the 625 prefix that signifies Holden part numbers.

A fresh 140-horsepower, four-carb engine looking neat and tidy. These engines were run in the 1965 to 1969 cars and were the most powerful of the stock, normally-aspirated engines.

The concept of an air-cooled rear-engine car had been well proven by the ’50s. Tatra, VW and Porsche, among others, had built successful cars using this system both before and after the war. Aircraft engines built by Continental and Lycoming had proven the air-cooled flat six to be a strong design.

From the beginning there was a persistent urban myth that Porsche or VW had a hand in the design of the car.

Bob Benzinger said, “I am often asked how much help we got from VW and Porsche. And sometimes asked this by people who firmly believe that Herr Doctor himself designed the vehicle, the engine, the whole shot. Actually, the truth is that zero help came from VW or Porsche.”

That said, in 1957 Chevrolet purchased a Porsche 356 to give it a look-over and pulled the engine to study it on the test bench.

The Corvair engine was developed long before Porsche came out with its six-cylinder engine for the 911. In fact, when Porsche was developing its six-cylinder 911 engine, Ferry Porsche had Huschke Von Hanstein purchase a Corvair for them to study. In 1961, Dan Gurney, who was driving the Porsche Formula One cars, brought a Corvair over to Germany to drive. So it is clear that Porsche had a good look at the Chevy when they were developing their engine.

The Corvair engine was laid out by the engine designer Al Kolb, who designed the Small Block Chevy. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest engine designers of all time, right up there with Leo Goosen, Vitorio Jano and Mark Birkget.

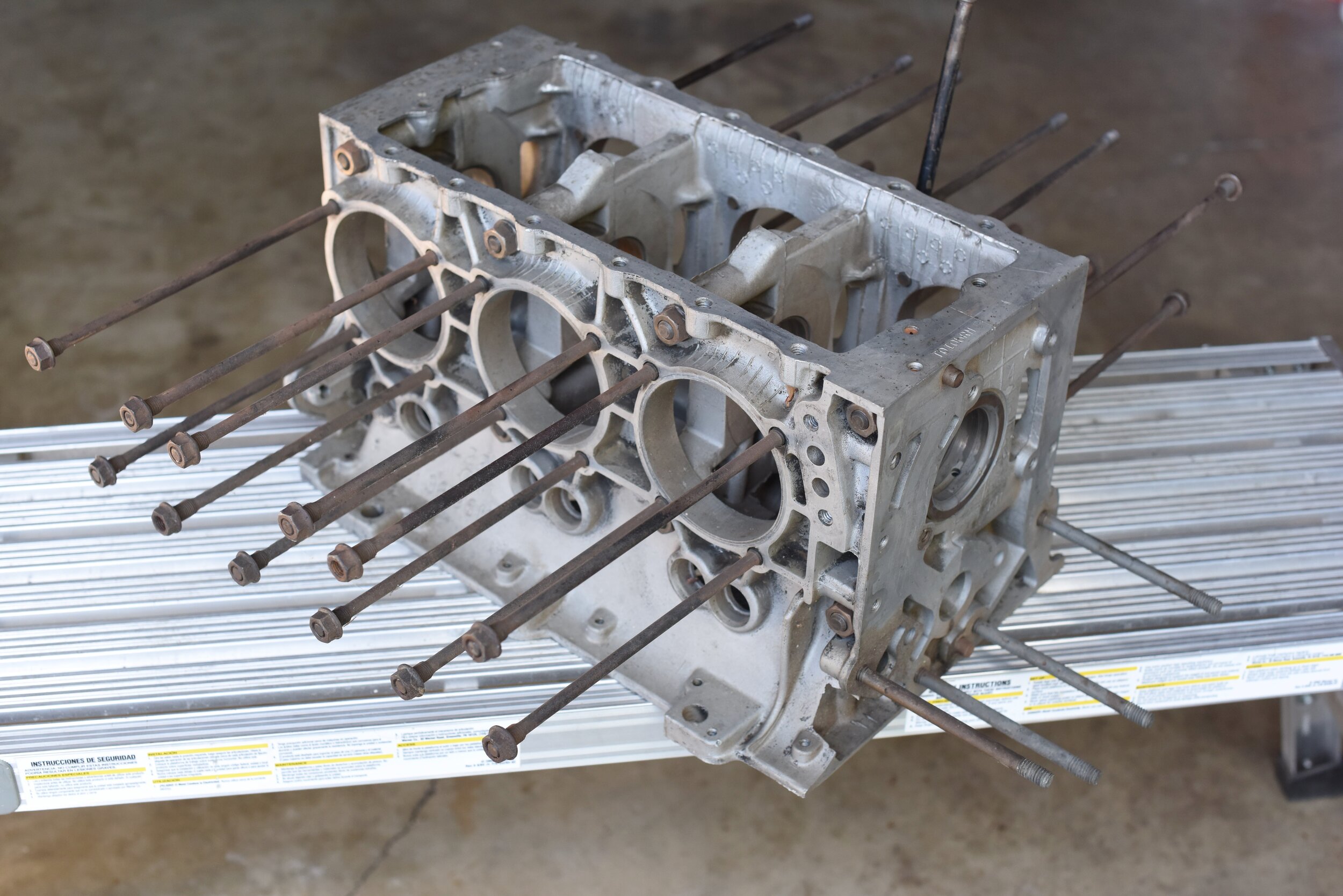

The bare engine block of the Corvair engine. This was GM’s first aluminum engine block.

Early on the team rejected a four-cylinder engine as too rough running and not powerful enough. U.S. customers demanded a certain level of performance, and a four would never get it.

There were several challenges that pushed the engineering staff in developing the engines. This was GM’s first alloy engine, and as such there was a learning curve with regard to working in aluminum. The air-cooled engine was also a first for the company, and this came with its own issues.

The Corvair uses cast-iron cylinders with an alloy block and heads. In an effort to keep costs down it was to be a pushrod engine instead of overhead cam. The difference in thermal expansion rates, exacerbated by the higher temperatures involved in air-cooled engines, is significant and had to be worked out. Things like working with permanent-mold casting, getting fasteners to stay in and keeping the bearings from coming out as the block expands were all issues that had to be figured out.

Of course these types of issues were not new; motorcycle engineers had been dealing with them for years, but they were new to the engineers at Chevrolet, who also had to gear up for volume production.

Because of the expansion issue the engine uses hydraulic-valve cam followers that compensate for the expansion rates without requiring constant valve adjustment and give a quieter-running engine.

Another problem was combustion-chamber and cylinder-head cooling. This is fairly straightforward with a four-cylinder engine but on a six it is much more difficult to cool the center cylinder and its exhaust valve.

In his speech, Benzinger discussed the issues they dealt with: “With a two-cylinder head, it's rather simple to dump, if you will, the exhaust immediately out with a very short fork, out the front and rear of the head and keep the center area of the cylinder head nice and cool with the incoming inlet mixture. But as soon as you put the third cylinder in that head you've wiped out all these neat ideas. Then you face the problem of dealing with heat: dissipating it, keeping the hardware cool - in a central area in the cylinder head.”

In the end sub-contractor TRW developed a more heat-resistant Nimonic steel alloy for exhaust valves so that they would not burn up. This steel was applied to many engines and resulted in better valves for GM cars.

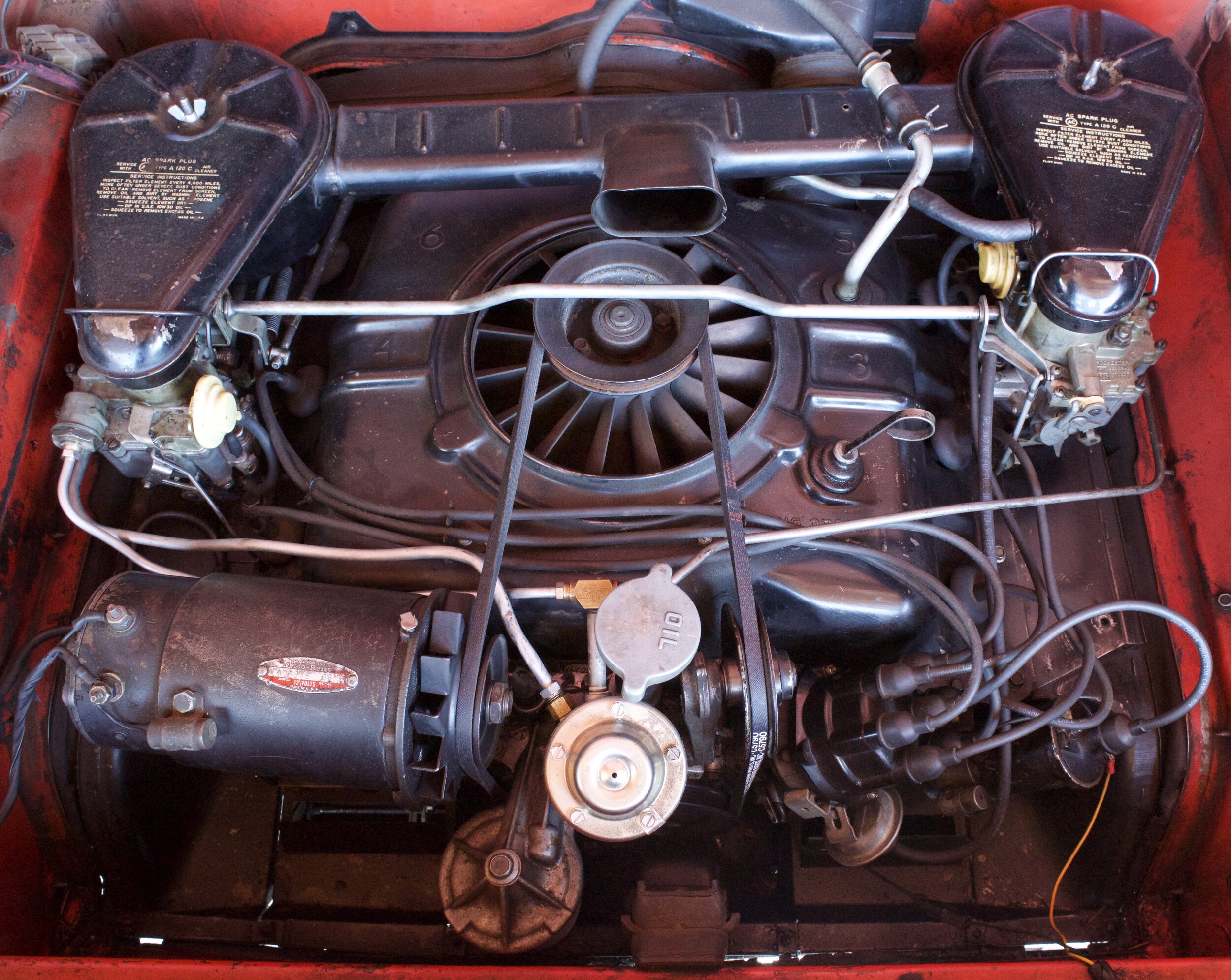

Twin-carb 110 horsepower engine in a late 1962 Corvair Monza. This car was one of the last of the ‘62 models made at the Oakland plant, and there are some details that are actually from the 1963 models as this was a transitional car. Note how the fan belt makes a 90-degree turn to run down to the crank pulley.

With an air-cooled engine you need to have a cooling fan. Development of this fan was crucial, and there were several challenges regarding its design, not least of which was how to drive it. In an effort to keep the engine low, the fan was laid horizontally on top of the engine. So how do you drive a fan that is on a plane 90 degrees from the drive pulley?

You can do it with a jackshaft driven off the crank, but that is expensive to make. A belt is the easy way to go.

The engineers came up with a clever solution. The belt wraps around the fan pulley, makes a 90-degree turn over the generator drive and dives down to and around the crank pulley, coming back 90 degrees over the tensioner pulley and back to the fan. The belt moves through 540 degrees of rotation. It is one of the things that the uninitiated seem to find most interesting when shown their first Corvair engine

A late version of the vacuum-cast aluminum fan that cools the engine.

Naturally, the belt was an issue, too. The inertia of the fan as the engine is revved wanted to break the belt or flip it off of the pulleys. There were a lot of belt-construction formulas tested by GM subcontractors before a suitable belt was designed. This resulted in better belt technology for all cars.

As with all revolutionary cars there was a long list of problems to solve: What was the best way to carburate the engine, carburetor icing, fan construction and engine sealing being just some of them.

“It was late in 1957 that we had the first engines running,” said Benzinger. “We used to figure that the gestation period for an engine was just about what we're used to from Homo Sapiens. It took about nine months from when you told the designers and drafting room to go until you had the design completed, experimental hardware built and the first engine running. So late in 1957 the first engine was running.”

After a period of development on the test bench the first engine was put into the Porsche that they had yanked the engine from and driven around the proving grounds. They did this because they did not yet have a body to put the engine in and because the Porsche did not draw too much attention from the press or public. Their biggest danger was Porsche owners who wanted to check out that weird-looking Porsche.

As launched in 1960 the engine was 140 cubic inches (2.3 liters) rated at 80 hp for the base-model car.

Almost immediately it was uprated to 144 cubic inches (2.4 liters). In ’64 it was bumped up to 163.7 (2.7 liters), where it would remain for the rest of the run.

There were several states of tune available depending on what the model was and the carb setup. Horsepower ranges from 80 horsepower for early base models to 180 hp for the final turbo cars.

A big pioneering area for Corvair was turbocharging. In 1962 Chevrolet introduced the slightly misnamed Supercharged Spyder engine, rated at 150 horsepower. This was a significant increase in power from the naturally aspirated engines.

Along with the Olds F-85 it was one of the first volume production turbocharged cars brought to market. The engine internals were beefed up and the compression reduced a bit to handle the extra pressure.

The engine bay of a turbocharged Spyder engine. A side-draft Carter YH carburetor feeds mixture through the turbo and into the heads. The turbo engine was confusingly labeled as supercharged by GM.

Turbocharging is a fairly inexpensive way to make more power. In simple terms the more air you can cram through an engine the more power it will make. But there is a danger. If you over-pressurize the engine you will blow it up. Most pressure systems use a wastegate that opens at a certain amount of boost, relieving the pressure and protecting the engine.

With the Corvair, Chevrolet used a simplified system that uses exhaust back pressure to limit turbo boost. They simply made the exhaust diameter small so it choked off the turbo before it could over-pressurize the engine.

When the new-model Corvairs were introduced, the turbo cars were bumped to 180 horsepower, making them the most powerful production models.

Design

While the engine was being designed and built, the styling department was working on the body. The first platform they put the engine in, after the Porsche, was a really ugly sedan that looked vaguely Holden. But it was just a placeholder development mule. The best was yet to come.

One of the funny things about design is that people say they want new and revolutionary things, new and revolutionary shapes, but in fact they don’t. What people want is the familiar, with a new twist. This is the famous Most Advanced Yet Acceptable (MAYA) concept of designer Raymond Loewy.

The author’s father-in-law, Jack Barnes, bought this 1961 sedan new for his family. Note the Flying Wing roof detail. This echoed the roof line of the rest of the GM line in an effort to give the Corvair an air of familiarity.

Chevrolet realized that if they were going to introduce a radical new concept into the market they would need to give it something familiar. So there are elements of the Corvair styling, like the curved A-pillars, the widely-spaced four headlights or the “Flying Wing” roof that match the company’s other products for 1960. If you take the greenhouse of the Corvair and overlay it on a ’59 Chevy it is almost an exact match.

The designers wanted to achieve a small car with a large passenger compartment. Not an easy thing to do. Most of the time this results in an awkward-looking car with a greenhouse that is too big. To put it another way, a car that is too tall for its length and width. Because they had positioned the drivetrain behind the passenger compartment and out of the way, the passengers could be placed lower in the car.

This allowed them to create a roof line that was more balanced and proportional. The rear of the car is slightly longer than the front, and this gives the car a forward-leaning profile: a jet-airplane look that implies motion standing still.

The 1960 Corvair was the first unibody car made by Fisher bodies, GM’s in-house body manufacturer.

The cooling fan laid flat enabled designers to get the rear decklid low. This is another element that gives the Corvair a familiar look and visually ties it to the rest of the GM product line.

There was a slight stumble at the very beginning. Originally the plan was for an automatic transmission only, but the Marketing Department insisted that there had to be a manual option. But Chevy still did not see the car as anything sporting, just simple transportation.

Sedans led the way in the first year with over 200,000 produced as opposed to just over 60,000 coupes. It was not until the introduction of the more “sporty” Monza option later in the year that coupe that sales really took off. And it was the Monza that would be the making of the Corvair line.

Travis Fowler’s 1964 500 outlaw coupe visiting Knight’s Foundry in Sutter Creek. The 500 was the Plain Jane model. Travis says they are popular for building racers because they weigh less than the fully optioned models. There is a big movement to keep and celebrate patina as a style in and of itself, but Corvairs are great platforms for building a custom.

By the second year, 1961 (the year that saw the introduction of the Lakewood station wagon as well as the Greenbrier van and the trucks), coupe production outstripped the sedans by 50,000 units, with the Monza coupe outselling all other models.

As revolutionary as the air-cooled flat-six engine was for the American market, it was the styling of the early model Corvairs that had the most lasting impact on the automotive world. It was drawn by Ned Nickels, who was overseen by the legendary Bill Mitchell, who in turn was overseen by the equally legendary Harley Earl. All three titans of American design.

While the design had little impact on designers in the U.S. (Chevrolet had been a little too successful in producing an American version of a European car) the rest of the world was wowed by the new car from America.

As Paul Niedermeyer in his 2019 article, “Automotive History: How the 1960 Corvair Started a Global Design Revolution,” points out: “The Corvair was the smash sensation of the 1959 Paris Auto Show and unleashed a wave of copycats on an unprecedented scale. It instantly eclipsed Pininfarina’s influential 1955 Florida coupe as the most significant influence in European design.”

There are period photos of the Corvair in European traffic, and it looks completely within the design context of the cars around it. It was a small car in America. But it was a big car compared to most of the products from Europe.

The two strongest elements of the early design are the high horizontal belt line that runs all around the body and the front end of the car, which features no grill opening for the radiator.

The horizontal belt line is a stylistic evolution of the 1959 GM big cars. The front of the hood has the same central dip line as the ’59 Oldsmobile. It was with the Corvair that the horizontal crease really became the dominant design theme. It gave the car a strongly horizontal look accentuated by the flat trunk and hood.

The Flying Wing roof on the first sedans was a strong design element as well, but it was too gimmicky to last. It was to be the coupe roofline that made a much bigger impact.

To my eye, the least successful element of the early model Corvair is the body treatment under the front bumper. The rocker curving away to the flat floor has a weak look to it. Conversely the rear end of the car is timeless. The pods for the taillights continue the jet-plane look, and the decklid is very strong with its louvers and proportions.

Within a year design elements from the Corvair began appearing on European cars. The first, and one of the most faithful tributes, was the ’61 NSU Prinz. But the NSU 1000TT and 1962 FIAT 1300/1500 sedan were right there as well. The FIAT has the high belt line surrounding the body with smooth flanks and four horizontal headlights. The Prinz is like a super-cute, downsized cartoon version of a Corvair.

The ’62 Simca 1000, Renault R8 and ’63 Hillman Imp all cadged the Corvair front end and the belt line. The ’63 Panhard 24c and 24tc look like slightly squashed Corvairs. The ’65 Peugeot 204 convertible took the belt line and the rear of the Corvair, and the ’66 ZAZ 966 from the Soviet Union is a Corvair copy from the waist down.

The most famous and lasting impact the Corvair had on European cars was on the 1964 Neue Klass BMWs. The BMW is a bit more blocky, but that strong horizontal high beltline crease with smooth flanks is pure Corvair. BMW has a shallower crease with trim on it, but it is still there, wrapping all the way around the body. The relationship between the large greenhouse and the body, and to a certain extent the front and rear treatments, are also strongly influenced by the Chevy. The BMW is just a logical smoothing of the design with a bit more height.

Right from the beginning, Chevrolet built concept cars including the Super Spyder, the Monza GT, the Monza SS Roadster and the fantastic Sebring Spyder. Some of the best designers at Chevrolet, including Larry Shinoda, did concept work with the Corvair platform. These cars had a significant influence on Corvair. First and certainly not least was the Monza concept that was rushed into production in 1960 to successfully bolster sales.

The Forward Control vans and trucks (in fact, all the Corvairs) are known for light and precise steering due to the low weight of the front end; another benefit of the rear-engine concept.

The Monza GT sports coupe in particular was a car that looked close to production reality, but it was clear that there was room for only one sports car at Chevrolet and that was the Corvette. They would brook no competition.

Pininfarina and Bertone produced successful design concepts that made the rounds of the car show circuit.

The engineers at Chevrolet tried several things, including a Sterling-engined car and an all-electric car.

There are also the specials made by racers Don Yenko and John Fitch.

Fitch was one of the most successful American racers of his generation. As a factory Mercedes driver, he competed and won at the highest levels of international competition, including Formula One and sports car racing. He had the opportunity to test the early Corvairs and saw potential. He purchased an early Monza and created the Fitch Sprint.

The Sprints were primarily street cars built on both the early and late platforms. You could buy a kit and install it yourself, have the dealership install it or take your car to Fitch’s shop in Connecticut and have them install it. One of the cool things about a Fitch Sprint kit is that they didn’t void the vehicle’s warranty.

Fitch’s ultimate goal was to produce his own coupe called the Fitch Phoenix with a bespoke chassis and Corvair running gear. Prototypes were made but he was never able to put it into production.

Unlike the Fitch Sprints, the Yenko cars were primarily racecars. Yenko, a longtime racer whose family owned a Chevy dealership in Pennsylvania, saw an opening in the SCCA regs and decided to make a run of race cars to compete in the D production class. In ’65 Yenko purchased 100 four-speed Corsas and stripped all the Chevrolet badging off of them. They were offered in different states of tune up to 240 hp.

The Corvair had been refused as a “sports car” by the SCCA, and Yenko’s cars had to be rebadged to be eligible for competition. They were extensively modified with engine and suspension upgrades and badged as Yenko Stingers. The Stingers were homologated by the SCCA and FIA, making them eligible for international competition.

In ’67 team driver Jerry Thompson brought home the SCCA D production title for the Yenko.

Yenko produced 130 or so cars in house along with a few cars that were brought in by customers to be modified.

The style and speed of the hardtop Corsa on the road.

In 1965 Chevrolet introduced the new-model Corvairs into the teeth of “Unsafe At Any Speed” and swirling controversy. As noted, the new model was a successful development with significant improvements to the engine and suspension.

The body design, largely the work of Ron Hill, was an absolute home run received warmly by the motoring press.

In the October 1964 issue of Car and Driver, David E. Davis wrote, “We have to go on record and say that the Corvair is in our opinion — the most important new car of the entire crop of '65 models, and the most beautiful car to appear in this country since before World War II. … The new rear suspension, the new softer spring rates in front, the bigger brakes, the addition of some more power, all these factors had us driving around like idiots — zooming around the handling loop dragging with each other, standing on the brakes — until we had to reluctantly turn the car over to some other impatient journalist. ... The '65 Corvair is an outstanding car.”

In a turnabout, the new design did not have the impact that the original car had. It was more popular in the States than it was in Europe where the first model was still having a measurable influence on automobile design.

The critics wished that Chevrolet had come up with more power. Ford was killing them with the V8 Mustang. But, as anyone who has had a late-model Corvair will tell you, the cars can be hustled along briskly. It is worth noting that unlike Porsche, whose stated aim was to build sports cars, the Corvair was still looked on as an economy car by GM.

While not strictly a sports car they are a fine GT and the engine responds well to tuning, so they can be made fairly rapid.

Despite the beautiful new body, the late-model cars didn’t sell as well as the earlier cars, mostly because by then GM was not really pushing them (they were full-bore behind the Camaro) and the car market was chasing the Pony Car segment like mad.

In the end Corvair died with a whimper. Killed by its production costs, and the Mustang, with a splash of Ralph Nader to help it sink.

All of which leads us back to the fact that for a car of this vintage the Corvair is undervalued. To some this is a bad thing. They want their cars to be worth more. But I think for many people it is a good thing. Vintage cars are just skyrocketing in value, and the Corvair is a chance to own a stylish car with a unique and significant history without breaking the bank.

It is a measure of how strong the Corvair community is that there is strong parts availability from several sources. There are active clubs and there are still good treasures to be found in garages, waiting to be brought back to life.

Recently there have been articles from sources like Bloomberg and the Hagerty Drivers Club magazine with market experts touting the Corvair as a good vintage car to get into; Why? You guessed it, because they are a significant car, undervalued and primed to go up in price.

There are a number of models out there for the Corvair enthusiast. Here a Hot Wheels version perches on the oil filler of a 140-horse Corvair engine.

Thanks to John Heiser, Travis Fowler, Eva McGuire, Dave Oyler, Wes Nicholas, Hagerty Insurance and GM Heritage for their invaluable help in producing this article.