Mark Osterman's MO-2025 film project

Image of the Roman Forum taken with a 1928 Leica using film recreated by film historian Mark Osterman.

Story: Mike Blanchard Photos: Mark Osterman

I first met Mark Osterman online when I sold him an early Leica FILCA 35mm film cassette. After messaging back and forth a few times he told me about the project he was working on. 2025 marks the 100th anniversary of the first production Leica. Osterman’s goal was to recreate the film Oskar Barnack used in the first Leica cameras.

Osterman, who lives and works in Rochester, New York, is uniquely qualified to take on this project.

He and his wife France Scully are the foremost experts on 19th century film processes. They have traveled all over the world teaching, appeared in documentaries and authored numerous articles on early film.

From 1999 to 2020, Osterman was the Film Processes Historian at the George Eastman house, the premier photographic museum in the United States and possibly the world.

For those of you who have not been there, the Eastman House, located in Rochester, has a massive collection of items related to photography. They have cameras that are rare and cameras that are historically significant, including an original Daguerre camera and the camera used to take the image of the flag-raising on Mount Suribachi during the battle for Iwo Jima.

In addition to cameras they have a large collection of reference material and photographs as well as the archives of many of important photographers of the 19th and 20th centuries.

“My job was to take things from the collection and learn things from them and make images,” said Osterman. “To research primary sources and early photographic processes and make them work. … For the first 10 years I was working with curators … teaching them how to conserve the photographs in their collections.

“After 10 years we began working with the public and giving workshops. We taught 26 workshops a year. … I had to come up with two extinct processes a year. A lot of the processes I taught, no one had done in modern times.”

During the COVID pandemic, Osterman’s department at the Eastman House was dissolved and he had to negotiate the separation. In the end he was able to retrieve his books and some things that belonged to him but not everything. He did his best to wrap up his projects and hand them off to his assistant, but in the end it all collapsed.

Osterman has been the owner of a Ford Model T since he was a teenager. This 1923 Runabout “Nellie” is his daily driver. He is excited to be able to carry out his work with the MO-1925 film using equipment from the ‘20s and driving it all around in a car from the same era.

Since then, he and Scully have carried on. “Now we do everything we did at the museum at home.” They travel all over the world teaching workshops on historic film processes.

The genesis of the MO-2025 project came from a trip to Turkey in January 2024. “We were in Istanbul teaching gelatin emulsions to a wealthy private client, working in an amazing darkroom for two weeks,” said Osterman. “He has two assistants to help, and a big collection of cameras.

“On his desk he had a 1930 1a Leica … the Hockey Stick. I had never held one. In my free time I would pick it up, just fiddling around with it. I liked it so much, the feel of it, the concept of it. Before we left I bought one on Facebook Marketplace from a guy in Boston. My friend picked it up for me before we got home.”

That 100-year-old Leica inspired him to recreate the film that Oskar Barnack was shooting in the first Leicas. Along with recreating the film Osterman’s goal was to use period gear throughout the project.

It might be obvious, but the first 35mm cameras used 35mm movie film. The Leica camera was designed to take advantage of the ready availability of that film stock but also to take advantage of the slow, fine-grained movie film. This type of film allows you to make large, sharp prints without having the hassle of a large, cumbersome camera.

The famous Leica concept of Small negative, large print was based on fine-grain film. The manual for the Model 1a recommends using slow-speed film unless shooting indoors or at motor racing events.

Post World War I Leica benefitted from an improvement in film emulsion that had seen film speed jump from ISO 1 or 2 up to ISO 10 or 12, which made it possible to hand-hold the new camera. The new miniature camera sparked a technical revolution in photography and photojournalism.

The film Barnack was using was orthochromatic film, which is only sensitive to blue light. This is why early film has a very specific look that is difficult to achieve with modern film.

Over a period of the last nine months Osterman pulled together the equipment needed to make 35mm film and has developed and tested the film. He has called his recreation film MO-1925, the prefix being his initials.

Osterman’s 1928 A model ”Hockey Stick” Leica with FODIS vertical rangefinder.

The camera was sent off to a reputable shop to get a CLA (clean, lube and adjust) and have the shutter curtains replaced. When the camera came back the film cassette wouldn’t go in all the way. A bit of investigation revealed that one of the screws holding the cover on was out of position and preventing the film cassette from going all the way in. “Most people said just use a modern cassette but that’s not what I’m doing.”

Once he got the screws back in the correct spots, Osterman loaded a roll of film in the camera, which promptly shredded the sprocket holes and filled the film chamber with bits of shredded film. Anyone familiar with Barnack Leicas knows what a pain that would be to clean up. So the camera went back to the repair shop, who checked it out and told him that it worked fine for them and there was nothing wrong with it.

When he got the camera back it promptly shredded another roll of film. Frustrated, Osterman posted photos online of the camera and asked if anyone had any ideas. After weathering the inevitable comments of “You are loading the camera wrong,” a repair tech reached out to him with the solution to the problem.

So he sent the camera off to the new repair guy and had the camera gone through again. The new guy was not a Leica specialist but he was dead right about the source of the troubles. As it turns out the spring that sits below the take-up spool was broken and out of place. The tech also found screws that were out of place and stripped from the original CLA.

Early Leicas are essentially hand-made devices that were assembled and fitted by craftsmen in the old way. This was before hyper-precision, computer-controlled CNC lathes and mills. Many of the parts and fasteners were hand-fit to work in a specific hole. You can’t just mix screws and parts up like they were interchangeable.

Osterman’s film coating machine spreads emulsion on a five-inch-wide strip of film and slits it into 35mm strips. Because the film is orthochromatic and not sensitive to red light the process can be carried out in safelight.

While the camera was being straightened out Osterman got to work on the other things he needed. Aside from the camera the main things he needed were film base, a machine to coat the film base, a slitter to cut it down to 35mm, a perforator to punch the sprocket holes in the film, period developing equipment and a period enlarger.

The enlarger was not much of a problem; with the rise of digital photography there are a slew of them floating around, often at bargain-basement prices. Darkroom equipment sells for very little, even vintage Leitz enlargers. After some hunting around Osterman was able to source a first model of Leitz variable enlarger from 1926. It was the third model Leitz made; the first two versions could only make one size of print.

Through contacts at Kodak Osterman was able to get a 1,000-foot roll of five-inch-wide Cellulose Acetate film stock.

The thing about Rochester is that almost everyone worked for either Kodak, Bell & Howell, one of the lens makers or Polaroid. Because of this there are bits of equipment tucked away in the most unlikely of places.

Osterman was able to get a small film coating and slitting machine that had originally come from Polaroid. At some point the machine was donated to the Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT) to teach students going into the industry. When RIT decided to clean house he got a call from a friend. “He said the machine was out on the curb.” He dashed over and got the machine before the scrap guys could get it.

The perforator was acquired through another series of unlikely events. Osterman has been a Model T Ford guy since his teens and these days his daily driver is a 1923 Model T Runabout he calls Nellie. So, as one does when one owns a Model T, he was out hunting up some T parts, which turned out to be junk. But the seller had a hot rod in his garage so they started talking cars.

A vintage perforating machine punches the sprocket holes in the blank film strip.

Turns out the guy had worked at Kodak in the Finishing Department where, among other things they perforated the film. The hot rodder had a friend who still worked at the plant with whom he would eat lunch once a week. In an amazing stroke of luck, the friend worked repairing and maintaining the perforating machines. Through this helpful Kodak employee Osterman was able to make a request for a perforator and damned if he didn’t get one. After a couple months he got a letter from Kodak giving him a perforation machine. He was taken to a building that contained a number of machines and given one.

“Kodak gave me a machine,” said Osterman, still a bit amazed that the company even considered giving him the thing. “It’s unheard of to get a machine with a letter from Kodak. Companies just don’t do things like that.”

Best of all the perforator has turned out to be an old machine that makes the same-shaped holes as the film made in 1925. At the beginning of the project Osterman had a bit of luck.

In the post World War II period Rolf Fricke was one of the foremost Leica collectors in the world. Fricke, who spent his whole career at Kodak, was of German extraction from Brazil and spoke German. He was a founding member of the Leica Historical Society of America and a personal friend of Günther Leitz, who would set up Leitz Canada for the company. Through his contacts at Leitz, and his position in the industry, Fricke was able to put together an important collection of rare Leitz and Leica equipment.

When he died, a large part of his collection was sold to Leica (where it now forms a significant portion of the company’s historic collection). But not everything. Osterman was able to get in touch with Fricke’s son Oskar and was was invited over to his late father’s house, which turned out to be an Aladdin’s cave of rare Leica accessories and equipment.

The rare FIMAN film developing apparatus. The drum is made of blown glass. The tray holds developer which the drum rotates through. The operator can watch the film developing and adjust development time by sight to get best results.

Sitting on Fricke’s desk was the first Leitz film developer. A vary rare bit of gear. This was exactly what Osterman needed and to find one in the States almost unheard of.

At first Oskar sold Osterman equipment but when he realized that Osterman was not getting the equipment to sell he pitched in to help the project.

“Eventually he said, ‘Come take what you want,’” said Osterman. “So now we have the film, the camera, the developing tank, the enlarger and a Model T to drive it around, all from the 1920s.”

As amazing as all that is, there was an even better bit of luck. Fricke was in possession of a roll of film taken by Oskar Barnack in 1914 as well as 10 rolls of film that had been shot in 1925 and 1926, using the first model of Leica, by a member of the Leitz family who ended up as company president. Oskar Fricke entrusted Osterman with those films to study. This is a holy grail moment. It is hard to overstate what an opportunity having access to a primary source of this significance means to a historian like Osterman. Among the subjects on the 1914 film are pictures of Barnack’s young son doing military drills with his classmates.

Rare historic roll of film collected by Rolf Fricke. It was taken by the inventor of the Leica Oskar Barnack in 1914. The image shows Barnack’s son and his classmates conducting a military drill excersize on the eve of World War One. The film stock was purchased by Barnack from the Bell & Howell company of Rochester N.Y..

On the technical side, inspection of the film showed that there was no halation so there had to be an anti-halation layer on the film stock. This layer of dye is washed away during developing. Another discovery was that the film stock had a distinctive sprocket-hole shape, which indicated that it was made on a Bell & Howell perforating machine.

In his research Osterman confirmed that in 1914, just before the start of The Great War, Barnack purchased some Bell & Howell movie film. The Barnack roll of film Osterman was studying had come from Rochester. The whole project was coming full circle from Rochester to Wetzlar and back to Rochester after 100 years.

Meanwhile, all the back and forth getting the camera straightened out caused a problem. The initial repair took months. “The project was all about shooting with a ’20s Leica,” said Osterman. “I was not able to make the 100-year anniversary at Wetzlar. The hard part was supposed to be the film, not the Leica.” In the end Osterman borrowed a Pre-War llla Leica to develop the film while his 1920s camera was being straightened out.

So lets go back to the beginning. When Osterman and Scully got back from Turkey in December of 2024 he began working on the film.

In his work at Eastman House Osterman had already recreated the gelatin emulsion used on movie film in the early ‘20s. That same emulsion was used in the first string-set Eastman Dryplate Cameras from 1887.

He had also made 35mm movie film. “When we first made it at Eastman and shot it in a 35mm SLR no one gave a shit,” said Osterman. “When we put it in movie cameras we were geniuses.” Movie film restoration folks were keen to see the process and learn about the film.

Osterman first tried his film emulsion on glass plates to test it out. This was before he added an anti-halation layer to the film.

He started by making the emulsion in his lab and coating glass plates with it. He shot the plates and the results looked good. So he coated some film stock and shot it with a Pentax SLR and that looked good but there was work to do.

“I realized I needed faster film,” said Osterman. The film speed started off fairly slow, ISO 1 or 2, but fairly quickly he was able to push it up to ISO 10 or 12 and higher. The first rolls had a lot of halation around the sprocket holes, which confirmed the need for an anti-halation layer.

Osterman and his wife have taught workshops in Sicily for a number of years. This year he decided to take some of his film and shoot it while he was in Europe.

“Two days before we left I made an anti-halation dye. I took two strips of film and brushed the dye on with a brush,” said Osterman. “I shot one roll in Sicily and one roll when we were in Rome. I’m not sure what the speed is so I bracket, but between (ISO) 15 and 20 I think. So it has exceeded my expectations.”

In the end Osterman was not able to make it to Wetzlar for the centennial celebrations with his film but he doesn’t seem too troubled by it. Despite not making his goal Osterman has continued to develop the MO-1925 film. There are some things he might try, like adding a dye that would make the film sensitive into the green-yellow spectrum, but he has no interest in making the film panchromatic, sensitive to all wavelengths of visible light. “It’s in nobody’s interest to make it panchromatic,” said Osterman.

“There is no logical reason to do any of this stuff except that’s what I want to do.”

That quote neatly sums up the whole project. It isn’t a financial venture. He doesn’t seem too interested in spreading his film around. The first thing I did when I found out about the project was ask for a roll, and he turned me down. No matter. For Osterman the whole point of developing this film is simply to do it and learn from it. In the end isn’t that what all artistic ventures should accomplish?

This story is just one aspect of what Osterman is doing. In addition to being a film historian he is a musician and instrument builder, a car restorer, an accomplished photographer and much more.

Find out more about Mark Osterman and France Scully at: https://www.collodion.org/

Before he left for Europe Osterman applied an anti-halation layer to the film with a brush. Note the shape of the sprocket holes is the same as the film taken by Barnack.

Because he is not sure of the film speed Osterman bracketed when shooting the first rolls of the MO-1925 35mm film. He thinks it is roughly 10-20 ISO. Further tests will establish a speed. The film is fine grained with beautiful mid-range tones.

The first model of Leitz variable enlarger with the original easel.

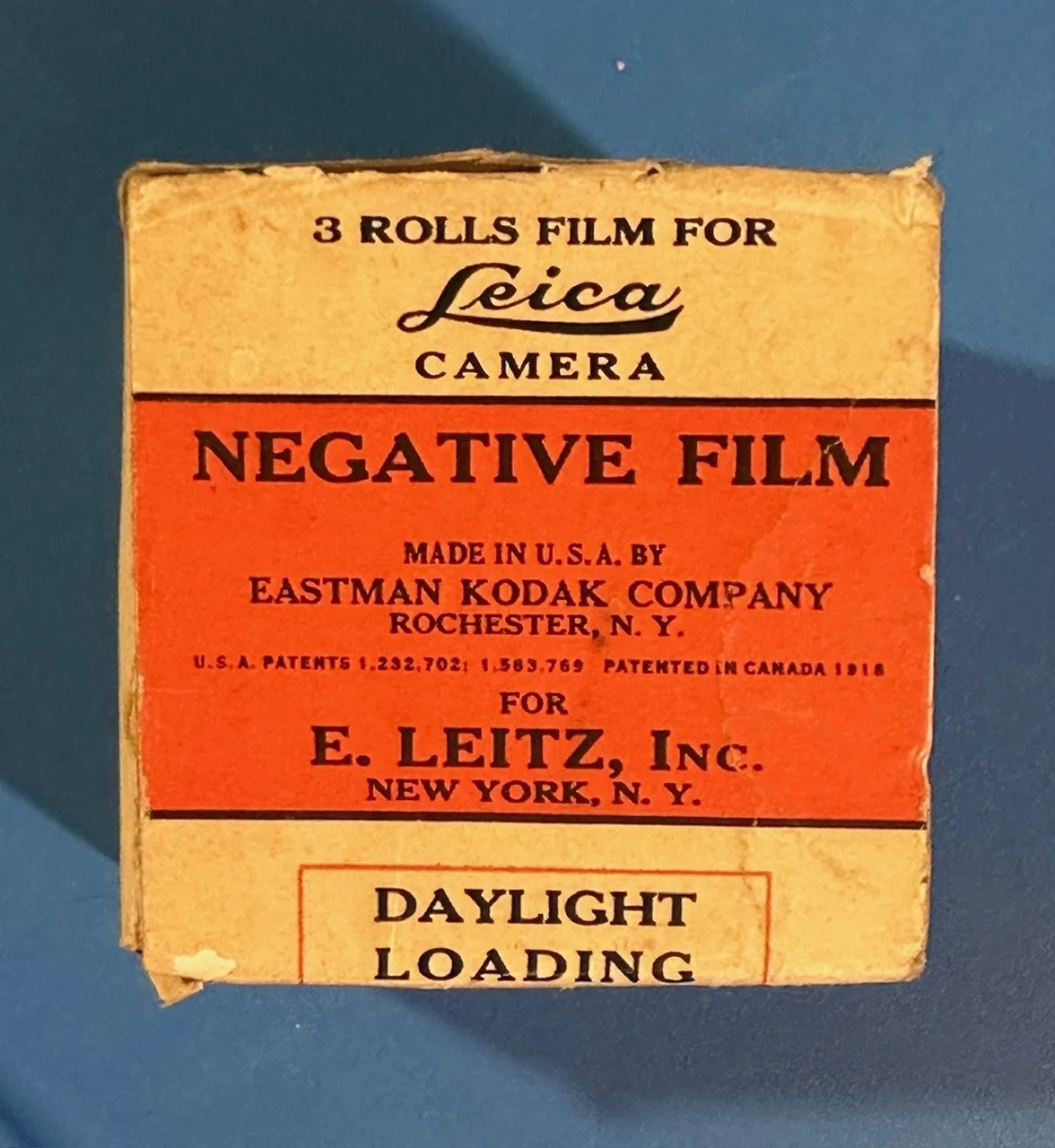

Kodak made film specifically for Leica cameras in the ‘20s